Of the over 500 species of bees found in Minnesota around 30% (147 species) are oligolectic (oh-LEE-goh-LECT-ic), or commonly referred to as specialists. Females of these species specialize in collecting pollen or floral oils from only one or a few types of plants. This means that the bee must be active at the right time and in the right place when their host plant blooms, and the flower must be the right shape for the bee to access it. Bees in the genus Macropis are unique in that they collect floral oil from their host plants in the native loosestrife genus (Lysimachia). The stakes are high for this relationship between bee and plant to work out: the bee’s offspring are counting on food from the flowers to be delivered to their nest!

This page provides more introductory information on bees, and a look-up function for some of the specialist bees native to Minnesota. Click on the bee name for more information on that species. The distribution maps on these pages are based on existing records; it is likely that species are present in other counties but have not yet been documented there. The Minnesota Biological Survey (MBS) is working to expand our knowledge of specialist bees and their distributions across the state. A a full list of bees, including oligolectic species in Minnesota, was produced in collaboration with the University of Minnesota Department of Entomology. The list (now with over 500 species) will continue to be updated as surveys are completed and specimen identifications are confirmed.

These pages aren’t intended to be used for species-level identification, although with practice, many genera can be recognized in the field or from photographs. Citizen science networks such as iNaturalist, Bumble Bee Watch, and BugGuide.net may help you report and identify bees through photo-sharing.

Eusocial bees like honey bees, and bumble bees produce colonies that cooperate to take care of young - with one queen and many specialized workers. Bumble bees (Bombus species) form annual colonies, with new queens starting new colonies in new locations each year that can grow to hundreds of individuals. Honey bees are not native to North America and form perennial colonies, with worker bees living through the winter, and can grow to tens of thousands of individuals. Note that the term “hive” refers to the often-manmade structure housing honey bees (Apis mellifera) only, and does not refer to the nest of any native species.

Solitary bees, which make up 90% of bee species globally, nest as individuals. Every adult female creates her own nest in which she lays eggs and deposits food for her young. All females can reproduce and there are no workers. Often, a large group of solitary bees will nest in aggregations – these are not colonies, but rather, many individual nests tended by individual females. Some bee species fall somewhere in between highly social and solitary. These semi-social bees may have numerous females from overlapping generations in a nest with a single entrance, but each taking care of their own brood.

Nearly 70% of native bee species nest underground. Nest entrances are typically on bare, exposed ground and resemble ant hills but with slightly larger entrance holes. Sometimes you can peak in and see a bee! Nests may be anywhere from several centimeters to over a meter underground.

About 30% of native bees nest as solitary individuals in cavities, usually hollow stems or holes found in dead trees. Some like carpenter bees can chew cavities with their jaws, but many depend on beetle-made holes for their nest cavities. Dead wood and wood boring insects, two things we tend to get rid of in our yard or landscapes, are highly important for cavity nesting bees. Plants with pithy stems, like sumac, blackberry, and elderberry, also provide important nesting sites.

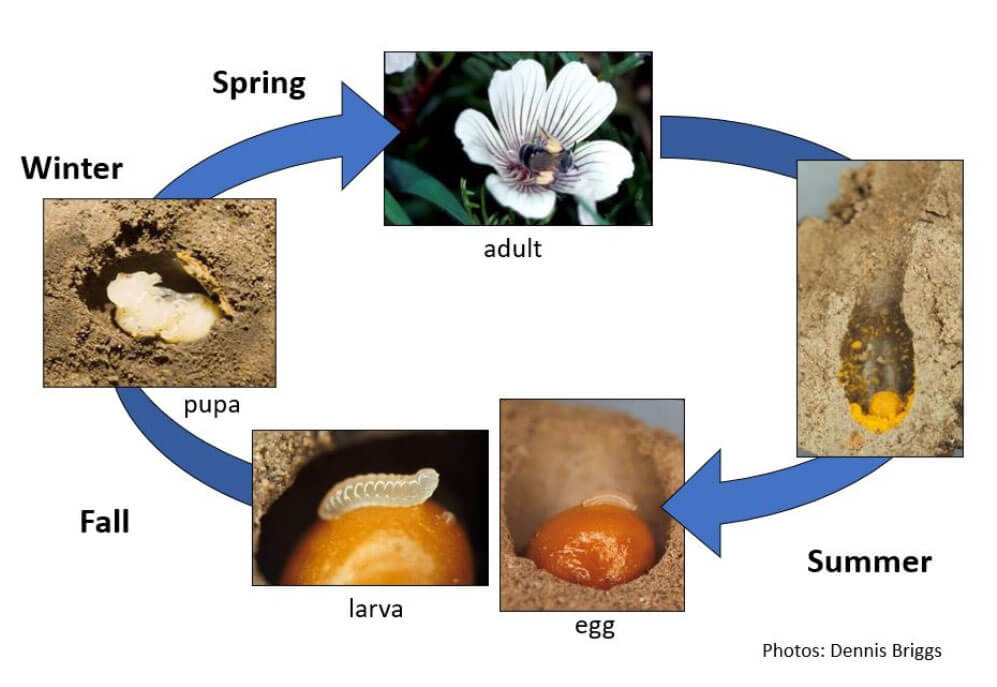

Solitary bees emerge at various times of the summer depending on the species. In general, once an adult female emerges, it will start making a nest either underground, in a hollow stem, or in another natural cavity. The bee will mate and forage for pollen outside the nest, returning to it to create a mass of pollen known as a pollen ball. On this pollen ball, a single egg will be laid and then closed off, creating a cell, like a room, where the egg will turn into a larva and pupa all while feeding on the pollen mass before emerging to spend a few weeks as an adult the following year. These cells are provisioned one by one and the number of cells varies by species.

Identification and bee terminology

Some bee species can be identified using photographic evidence without the need to collect specimens, but many other species require viewing under a microscope by trained experts. Bees are diverse and often tiny, but these aren’t the only challenges encountered when trying to identify them. Identifying characteristics such as the texture of the exoskeleton, type and location of hairs, and even the number of “teeth” can only be seen with magnification.

Many specialist bees are best identified in conjunction with their host flower, though a positive identification of most species without microscopic features is unlikely. These pages aren’t intended to be used for species-level identification although with practice, many genera can be recognized in the field. Citizen science networks such as iNaturalist, Bumble Bee Watch, and BugGuide.net may help you report and identify bees through photo-sharing.

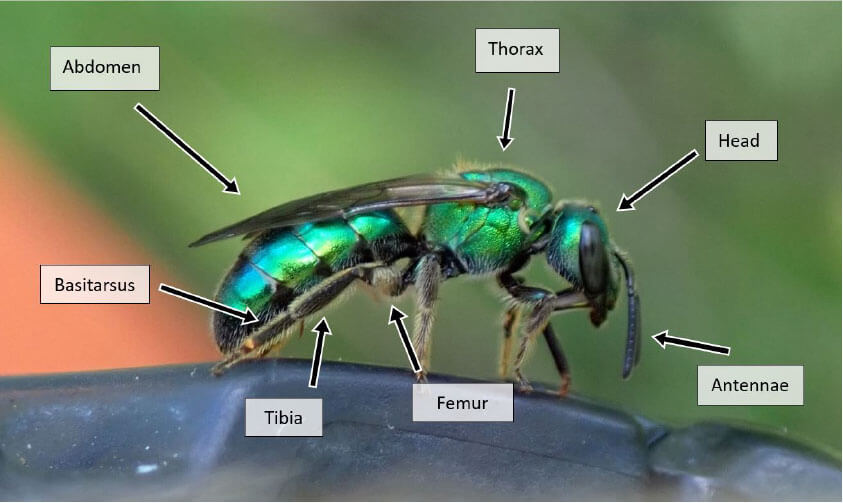

- Integument – the surface of the body, not the hairs

- Abdomen – made up of segments called tergites and sternites, stinger at the apex of the abdomen on females

- Thorax – middle section of a bee, where all six legs attach to the body

- Head – contains compound eyes, ocelli, antennae, face – clypeus, facial fovea (Andrena and others)

- Legs – Segments include femur, tibia, and basitarsus (plural basitarsi)

- Scopa (scopal hairs) – pollen collecting hairs, often long and feathery, located on various segments of the hind leg, apical portion of the thorax, or underside of the abdomen

Bee profiles

| Name | Host Plant | Season |

|---|---|---|

| Andrena andrenoides (Colourful Willow Miner Bee) | Salix | Spring |

| Andrena bisalicis (Eastern Willow Miner Bee) | Salix | Spring |

| Andrena carolina (Carolina Miner Bee) | Vaccinium | Spring |

| Andrena distans (Distant Miner Bee) | Geranium | Spring |

| Andrena erigeniae (Spring Beauty Mining Bee) | Claytonia | Spring |

| Andrena fragilis (Fragile Mining Bee) | Cornus | Summer |

| Andrena frigida (Frigid Mining Bee) | Salix | Spring |

| Andrena geranii (Waterleaf Mining Bee) | Hydrophyllum | Spring |

| Andrena helianthi (Sunflower Mining Bee) | Helianthus | Late Summer |

| Andrena integra (Bare Dogwood Miner Bee) | Cornus | Summer |

| Andrena mariae (Maria Miner Bee) | Salix | Spring |

| Andrena parnassiae (Parnassia Miner Bee) | Parnassia | Late Summer |

| Andrena platyparia (Plated Miner Bee) | Cornus | Summer |

| Andrena vernalis (Golden-Alexanders Mining Bees) | Zizia | Spring |

| Andrena wellesleyana (Wellesley Miner Bee) | Salix | Spring |

| Andrena ziziae (Golden-Alexanders Mining Bees) | Zizia | Spring |

| Calliopsis nebraskensis (Nebraska Vervain Calliopsis Bee) | Verbena | Summer |

| Colletes aberrans (Aberrant Cellophane Bee) | Dalea | Late Summer |

| Colletes andrewsi (Andrews' Cellophane Bee) | Heuchera | Summer |

| Colletes latitarsis (Broad-footed Cellophane Bee) | Physalis | Summer |

| Colletes nudus (Sumac Cellophane Bee) | Rhus | Summer |

| Colletes susannae (Susan's Cellophane Bee) | Dalea | Summer |

| Dianthidium simile (Northeastern Pebble Bee) | Helianthus | Late Summer |

| Dufourea monardae (Beebalm Shortface Bee) | Monarda | Summer |

| Dufourea novaeangliae (Pickerelweed Shortface Bee) | Pontederia | Summer |

| Macropis nuda (Dark-legged Yellow Loosestrife Bee) | Lysimachia | Summer |

| Macropis patellata (Patellar Oil-collecting Bee) | Lysimachia | Summer |

| Megachile campanulae (Bellflower Resin Bee) | Campanula | Summer |

| Melissodes apicatus (Pickerelweed Long-horned Bee) | Pontederia | Summer |

| Melissodes denticulatus (Denticulate Longhorn Bee) | Vernonia | Summer |